Chapter 3 (Part 5): The Lucas Cultural Arts Museum

“I thought a museum was a concept that people already bought into about 200 years ago. They’re having us do as much work as we can hoping that we will give up. […] They hate us.” – George Lucas

Like the Fishers, filmmaker George Lucas wanted to build a museum in San Francisco’s Presidio. Lucas wanted to bring his Lucas Cultural Arts Museum to Crissy Field – a beach-front portion of the Presidio National Park with killer views of the Golden Gate, Alcatraz, and the Bay. Lucas must be reading Eli Broad’s museum-building playbook: After Lucas’s proposal was rejected he threatened to take his museum and collection to another city. Will billionaire Lucas get what he wants by leveraging cities against one another? Remember those sweet deals Santa Monica and Beverly Hills offered Eli Broad when he was “considering” them instead of Downtown for his museum? We know how that turned out.

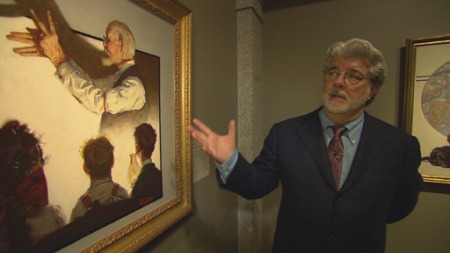

Lucas was making plans for his museum in 2009, but didn’t make a formal proposal until the Presidio Trust, which oversees and maintains the Presidio, sent out an RFP for the Crissy Field location. By March of 2013 16 proposals had been submitted, and by September those had been narrowed to three including Lucas’s museum. Lucas’s proposal was for a new Beaux-Arts-style museum to house his collections of illustration (lot of Norman Rockwell) and film ephemera (heard of Star Wars?). Lucas was willing to spend $700million: $300M for construction and $400M to endow it–he was good for it too, having sold the Star Wars franchise and Lucasfilm to Disney in 2012 for $4.05 BILLION dollars… Read the rest of this entry »

Chapter 3 (Part 3): Alice Walton & Crystal Bridges

“I’m Alice Walton, bitch.”[i] – Alice Walton, 2007

Alice Walton is the youngest daughter of Sam Walton, founder of Wal-Mart. She was raised in Bentonville, Arkansas—also the location of the first Wal-Mart, and where Wal-Mart corporate headquarters is located. In the past decade Walton has been on a shopping spree of American art, from colonial to contemporary.[ii] The spree was fueled by her philanthropic project, the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art (she chose the name), also in Bentonville, a city with a population of 35,000. The cost for the project is unknown, but art blogger Lee Rosenbaum (CultureGrrl) investigated the museum’s 990s and revealed that between 2005 and 2010, the museum spent $508.57 million in “expenses for charitable activities”[iii]—an intentionally vague category. These activities most like are the acquisition of art but also the design and construction of the museum by architect Moshe Safdie.